Sustainability Series: Acrylic yarn

Acrylic yarn is perhaps the mostly widely available fibre on the market today. It’s generally affordable, durable and easy to care for making it the fibre of choice for many. It’s a great choice for beginner crafters as it sits on needles nicely and if you need to frog it, it’s not a chore. But the properties which make it a good yarn also make it a pollutant. It’s persistent in the environment (meaning it takes a long time to break down) and it sheds microplastics which accumulate in soils and aquatic environments. The scary thing is now microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found in the food we eat (Cauwenberghe and Janssen, 2014), in sediments (Yao et al, 2019) meaning eventually there will be plastic markers in rock (Trinastic, 2015) and a plastic bag has even been found at the bottom of the Mariana Trench (info here).

As a community which is centred around curating slow fashion in a meaningful and sustainable way, it’s important that we become more familiar with the yarns we use. Even as an environmental scientist and an avid crafter, I knew very little about acrylic yarn other than ‘it’s plastic’. So, prepare yourself for some yarn science (coined by Sophie from @knit.purl.girl) and enjoy the confidence knowledge can give you when you next choose some yarn.

What is acrylic yarn?

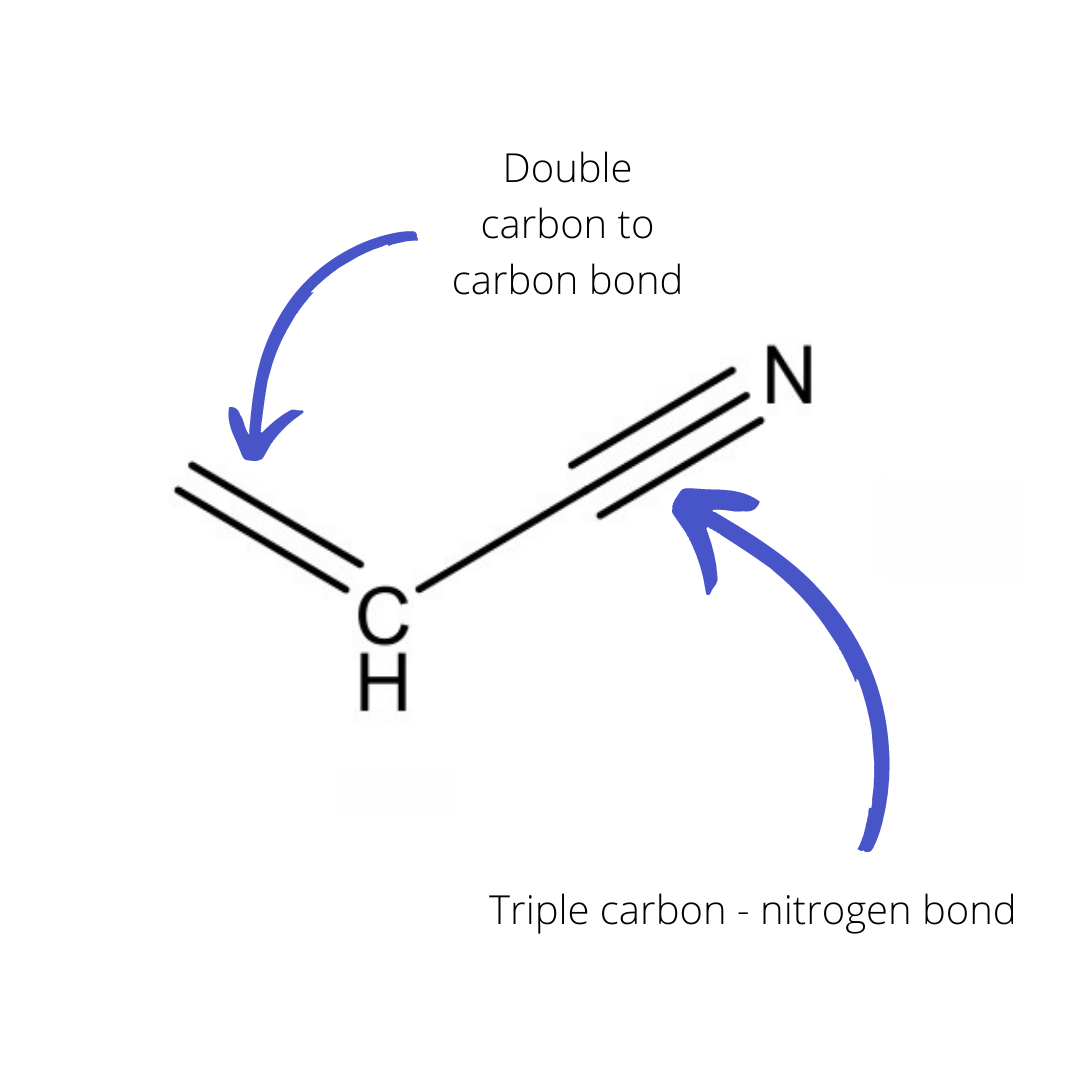

Acrylic fibres are made from synthetic polymers (i.e. plastics) derived from fossil fuels. The basic building block of these polymers is acryonile (figure 1) and it’s persistence in the environment can be attributed to the double and triple carbon-carbon and carbon-nitrogen bonds. There are various ways of producing acrylic fibres, many of them using either hydrogen cyanide or propylene and ammonia and require high temperatures and are therefore energy intensive. Acryonile can be spun into fibres using organic solvents (which require specialist disposal), metallic salts or hot air.

Figure 1. The Acryonile monomer - consider a monomer as a single stitch and a polymer as a row of knitting.

The qualities of acrylic fibres which makes them so useful makes their disposal difficult – they’re wear resistant, have strong resistance to sunlight, are resistant to biological and chemical agents meaning they do not easily undergo (bio)degradation and take a very long time to breakdown. The exact time it takes for this to occur will depend upon environmental conditions (temperature, pressure, moisture for example) and the exact structure of the plastic fibre and it’s hard to find a definitive answer because there isn’t one.

Acrylic yarn as a source of microplastics

Microplastics are a significant source of pollutant in both marine and terrestrial environments. They can enter the environment directly (for example microbeads in cosmetics) or through the fragmentation of larger plastics where they can persist and bioaccumulate and are generally to be considered to be plastics smaller than 5 mm. It’s a relatively new problem and subsequently, the science is still in it’s infancy and the long-term impact of plastic pollution is unclear. It is possible that plastic may: be a vector for chemical contaminants, promote the growth of microorganisms as it provides a surface for biofilms to grow as well as cause ingestion problems at all levels of the food chain. What is clear however, is that microplastics are ubiquitous in our environment and that we really need to do something about it.

The release of microplastics through the washing of synthetic textiles has been proven but it is difficult to quantify. It occurs through a process known as pilling (basically when your clothes become bobbly) which arises from mechanical action from washing and/or wear. This will happen regardless of what your items are made from and will eventually happen to even the most expensive of clothing.

Microplastic fibres have been found in sediments, organisms and in water sources (Browne et al., 2011) and in wastewater entering sewage treatment plants (Dris et al, 2015). It have shown the microplastic fibres are released during washing of clothing made of acrylic and polyester at 30°C, 40°C and with and without detergent with more fibres being released when bio-detergent and fabric conditioner were used (Napper and Thompson, 2016). It is estimated that 720,000 fibres are released in a 6 kg washing load and these are on average 5.44 mm in length and 14.05 µm in diameter. What is unclear though is how much of this 6 kg of washing consists of acrylic garments and at what stage of their life the garments were at (early washes tend to produce more fibres). When I was researching this, this number (720,000) seemed to pop up a lot but no one had cited where it was from or how it was calculated. It’s a lot for sure and it is significant when you consider how often you do washing and how many wash loads per day or being done worldwide. A quick google shows that there are 83,000 households currently in York (city in the UK where I live), and assuming each household does an average of 4 wash loads (each at 6 kg) per week, that’s approximately 239,000,000,000 fibres released (yes you read that correctly – 239 billion). This of course makes a lot of assumptions and really it’s impossible to work out the real scale of the issue. But it’s a huge problem and it’s a hidden one.

Should I stop crafting with acrylic yarn?

A simple answer is if you can – yes. But it’s a little more complicated than that. Acrylic yarns are generally more accessible – you’ll find them in all crafting shops, non-specialist shops (I’m thinking Wilkos if you’re from the UK and Boyes if you’re from North Yorkshire) and they’re cheaper. My opinion is that it’d be better for people to create their own clothes with acrylic yarn and cherish them than to go to Zara and buy a sweater. Creating your own clothing makes you feel more connected to it and other things you own, therefore needing to buy less. Lower consumption is kinder on the environment.

Affordable alternatives to 100% acrylic yarn (just a couple of my favourites)

Drops Nepal - Aran weight 65% wool, 35% alpaca

Drops Puna - DK weight 100% alpaca

Rico Creative Cotton - Aran weight, 100% cotton

Cascade 220 - Aran weight 100% wool (A little more expensive but it’s a favourite and not talked about much!)

I think that should answer the questions I had about acrylic yarn. As I said on Instagram, this series is simply to educate and also to open up the conversation around sustainability and the yarncraft community. This is only the first instalment of many so as time goes on, my opinions may change or I may no longer deem yarns I’ve recommended as suitable. But this is a learning process and one which I’m happy to be on.

Please feel free to leave any comments or questions or anything you think I’ve missed.

Hope you learnt something and will come back to join me for the next instalment.

Abbie xx